Dr. Pakeeza Saif

King Edward Medical College, Lahore, Pakistan

Amin H. Karim MD

Houston Methodist Academic Institute

and Weill Medical College of

Dear Dentist: My Murmur Doesn’t Need Meds Anymore!

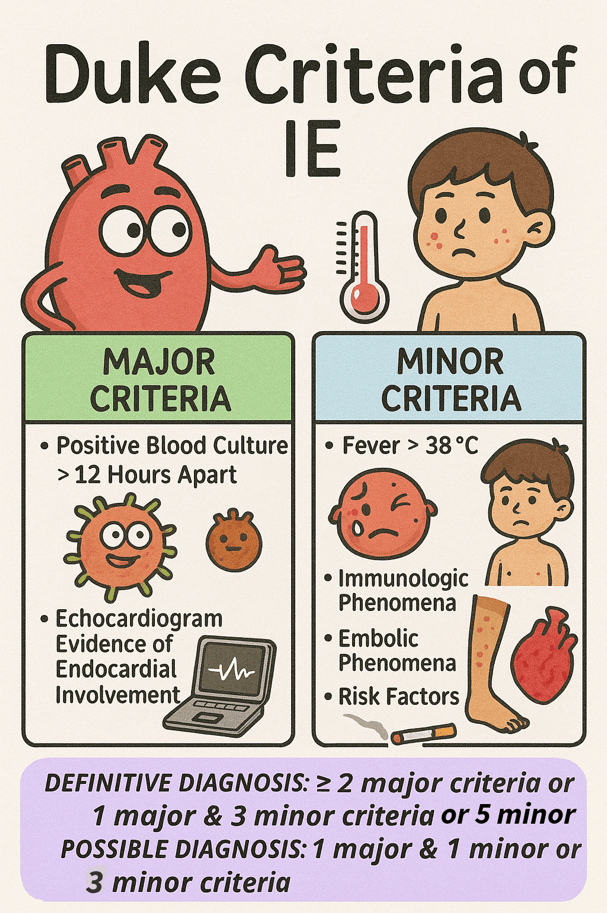

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a serious infection of the heart’s inner lining, affecting 3 to 10 people per 100,000 annually. It carries a significant risk, with mortality reaching up to 30% within the first 30 days 1 . Staphylococcus aureus was the most frequently identified pathogen, accounting for 31% of cases. The mitral valve was the most commonly affected, involved in forty-one percent of infections, while the aortic valve was affected in thirty-eight percent of cases 2. The diagnosis of IE is primarily clinical and is based on the modified Duke criteria, which include a combination of major and minor clinical, microbiological, and echocardiographic findings.

Guntheroth et al. observed that bacteremia was present in 40% of 2,403 cases following tooth extraction, 38% of individuals during routine mastication, and 11% of those with oral sepsis in the absence of any dental intervention 3. This issue has long concerned both dentists and cardiologists, driven in part by a preference for commission bias—favoring action over inaction—when considering prophylactic antibiotic use.

American Heart Association revised the guidelines on infective endocarditis prophylaxis in 2007 (full guidelines available at http://circ.ahajournals.org ) to promote the judicious use of antibiotics, particularly in clinical scenarios where the anticipated benefits are outweighed by the risks, such as the emergence of antibiotic resistance and the potential for adverse drug reactions. The present revised document was not based on the results of a single study but rather on the collective body of evidence published in numerous studies over the past two decades. The following points were used as a rationale by AHA for updating the guideline4.

- IE is much more likely to result from frequent exposure to random bacteremia associated with daily activities such as chewing food, tooth brushing, flossing, use of toothpicks, use of water irrigation devices, and other activities than from bacteremia caused by a dental, gastrointestinal (GI) tract or genitourinary (GU) tract procedure.

- Prophylaxis prevents only an exceedingly small number of cases of IE, if any, in individuals who undergo a dental, GI tract, or GU tract procedure.

- The risk of antibiotic-associated adverse events exceeds the benefit, if any, from prophylactic antibiotic therapy except in very high-risk situations.

- Maintenance of optimal oral health and hygiene may reduce the incidence of bacteremia from daily activities and thus the risk of IE and is more important than the use of prophylactic antibiotics for dental procedures 4.

Several studies have demonstrated that the lifetime risk of infective endocarditis (IE) varies significantly depending on the underlying cardiac condition. In the general population without known heart disease, the risk is approximately 5 cases per 100,000 patient-years. Patients with rheumatic heart disease (RHD) face a substantially higher risk, ranging from 380 to 440 cases per 100,000 patient-years, which is comparable to the risk observed in individuals with mechanical or bioprosthetic heart valves (308 to 383 cases per 100,000 patient-years)5 .

The greatest risks are observed in the following groups:

- 630 cases per 100,000 patient-years following cardiac valve replacement for native valve IE

- 740 cases per 100,000 patient-years in patients with a history of previous IE

- 2,160 cases per 100,000 patient-years in patients undergoing prosthetic valve replacement due to prosthetic valve endocarditis

These variations in risk highlight the importance of tailoring preventive measures to individual patient profiles.

Further research indicates that even with perfect effectiveness, antibiotic prophylaxis would prevent only a negligible number of infective endocarditis cases—given that the estimated absolute risk after a dental procedure is about 1 in 1.1 million for mitral valve prolapse, 1 in 475 000 for congenital heart disease, 1 in 142 000 for rheumatic heart disease, 1 in 114 000 for prosthetic heart valves, and 1 in 95 000 for those with a history of endocarditis6 7 .

Cardiac Conditions Associated with the Highest Risk of Adverse Outcome from Endocarditis for Which Prophylaxis Is Reasonable

- Prosthetic cardiac valve or prosthetic material used for cardiac valve repair

- Previous Infective Endocarditis

- Cardiac transplantation recipients who develop cardiac valvulopathy

- Congenital heart disease (CHD)

- Unrepaired cyanotic CHD, including palliative shunts and conduits

- Completely repaired congenital heart defect with prosthetic material or device, whether placed by surgery or by catheter intervention, during the first 6 months after the procedure

- Repaired CHD with residual defects at the site or adjacent to the site of a prosthetic patch or prosthetic device.

Guidelines also clearly stated that antibiotic prophylaxis is no longer recommended for any other form of congenital heart disease which explicitly includesheart murmurs, valvular regurgitation, or stenosis without prosthetic material or prior endocarditis 4.

Preventing Infective Endocarditis: Procedures Requiring Antimicrobial Prophylaxis

High-Risk Procedures Requiring Antibiotic Prophylaxis

- Dental procedures that involve manipulation of gingival tissue or the periapical region of teeth or perforation of the oral mucosa

- Respiratory tract procedure with incision and biopsy such as tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy

- Gastrointestinal or genitourinary procedures in setting of active infection

- Surgery on infected skin, skin structure, or musculoskeletal tissue

Low-Risk Procedures Not Requiring Antibiotic Prophylaxis

- Gastrointestinal or Genitourinary procedure in the absence of infection

- Most Vaginal deliveries or Caesarian deliveries

- Left atrial appendage occlusion device placement (e.g., Watchman) in the absence of infection — associated with a very low incidence of infective endocarditis, with long-term studies showing no device-related infections over extended follow-up. A single center, 14 year study of 181 patients found no device-related infections over more than 500 patient years of follow up8 .

- Stable cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) such as pacemakers and ICDs — antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended for dental or mucosal procedures solely due to the presence of a CIED in the absence of other high-risk cardiac conditions9 .

- Atrial septal defect (ASD) closure devices beyond 6 months post-implantation — prophylaxis is not indicated once the device is fully endothelialized and no residual shunt remains10 .

Infective Endocarditis Prophylaxis: Antibiotic Recommendations

- First line: 2 g amoxicillin orally (or 50 mg/kg kids) 30–60 minutes before the procedure.

- If allergic to penicillin, 600 mg clindamycin orally (or 20 mg/kg kids).

- Alternatives include 500 mg azithromycin or clarithromycin orally (15 mg/kg kids)

- If you can’t take pills, get 2 g ampicillin IM/IV (or 50 mg/kg kids)

Considering rising antimicrobial resistance and the potential for Clostridioides difficile infection linked to antibiotic use, it is advised against relying on the outdated “better safe than sorry” approach to prophylactic antibiotic use, as it may cause more harm than benefit to patients.

References

1. Mostaghim AS, Lo HYA, Khardori N. A retrospective epidemiologic study to define risk factors, microbiology, and clinical outcomes of infective endocarditis in a large tertiary-care teaching hospital. SAGE Open Med. 2017;5. doi:10.1177/2050312117741772

2. Murdoch DR. Clinical Presentation, Etiology, and Outcome of Infective Endocarditis in the 21st Century. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):463. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.603

3. Guntheroth WG. How important are dental procedures as a cause of infective endocarditis? Am J Cardiol. 1984;54(7):797-801. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(84)80211-8

4. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of Infective Endocarditis. Circulation. 2007;116(15):1736-1754. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183095

5. Steckelberg JM; WWR. Risk factors for infective endocarditis. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 1993;7(1):9-19.

6. Pallasch TJ, Wahl MJ. Focal infection: new age or ancient history? Endod Topics. 2003;4(1):32-45. doi:10.1034/j.1601-1546.2003.00002.x

7. Pallasch TJ. Antibiotic prophylaxis: problems in paradise. Dent Clin North Am. 2003;47(4):665-679. doi:10.1016/S0011-8532(03)00037-5

8. Ward RC, McGill T, Adel F, et al. Infection Rate and Outcomes of Watchman Devices: Results from a Single-Center 14-Year Experience. Biomed Hub. 2021;6(2):59-62. doi:10.1159/000516400

9. Canpolat U. Tailored antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing CIED implantation: One size does not fit all the principle. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 2019;42(4):483-483. doi:10.1111/pace.13624

10. Tanabe Y, Sato Y, Izumo M, et al. Endothelialization of an Amplatzer Septal Occluder Device 6 Months Post Implantation: Is This Enough Time? An In Vivo Angioscopic Assessment. Journal of Invasive Cardiology. 2019;31(2). doi:10.25270/jic/18.00206