Closed Case Study

by Olga Maystruk, Designer and Brand Strategist, and

Ariana Gutierrez, Risk Management Representative

Presentation

A 55-year-old man came to Family Physician A with a two-month history of occasional 2-minute-long chest pains after exertion. He described the pain as suffocating, sharp, stabbing, and radiating to his jaw, throat, and teeth. The patient had also experienced loss of consciousness, wheezing, stress, fatigue, and anxiety. The evening before the visit, he had a syncopal episode.

The patient’s medical history included hypertension, obesity, and lung disease; his family history was significant for heart disease, including a parent having a heart attack and a coronary artery bypass surgery. The patient’s blood pressure was 197/107 mm Hg and pulse 92. His BMI was calculated as 41.4. It had been three years since his last appointment with Family Physician A.

Physician action

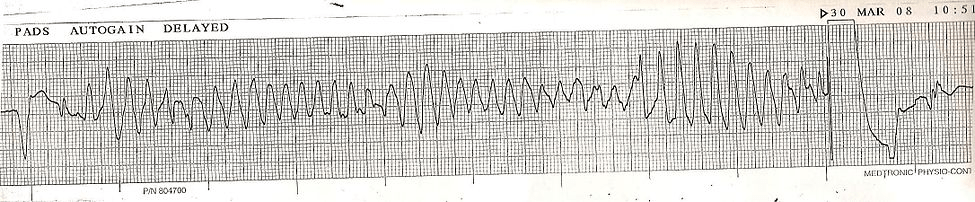

The physician ordered an EKG and lab studies. The EKG results showed a sinus rhythm, left axis deviation, left anterior fascicular block and possible septal myocardial infarction (MI). There were no acute ST-T wave changes. The lab results were all in abnormal ranges. Family Physician A referred the patient to cardiology to be seen the same day.

The patient saw Cardiologist A that afternoon. Upon examination, Cardiologist A documented left side chest pain, reproducible on palpation, and elevated blood pressure of 178/102 mm Hg. She documented that the EKG results showed a sinus rhythm, left axis deviation, and left anterior fascicular block with non-specific ST-T wave changes inferiorly.

Cardiologist A diagnosed the patient with hypertension, atypical chest pain, vasovagal syncope, and morbid obesity. The patient was prescribed valsartan-hydrochlorothiazide 12.5mg daily and instructed to return in three days for an EKG and stress test.

Upon checkout, the patient requested that his follow-up appointment be rescheduled to a later date. The patient was instructed to seek emergency care for any chest pain or shortness of breath.

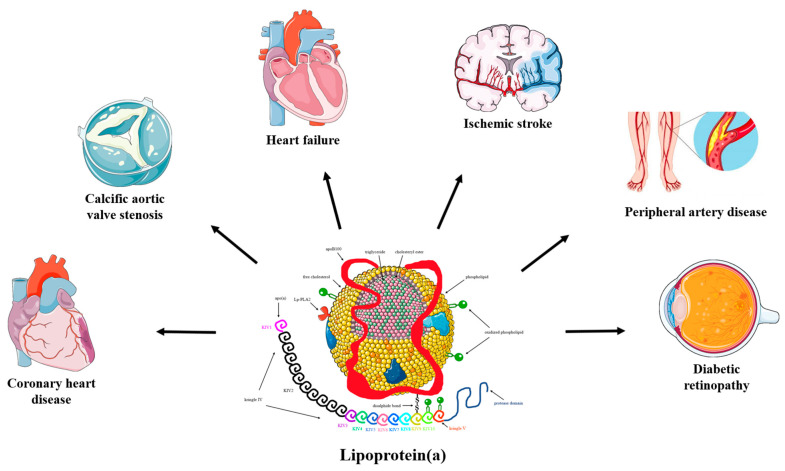

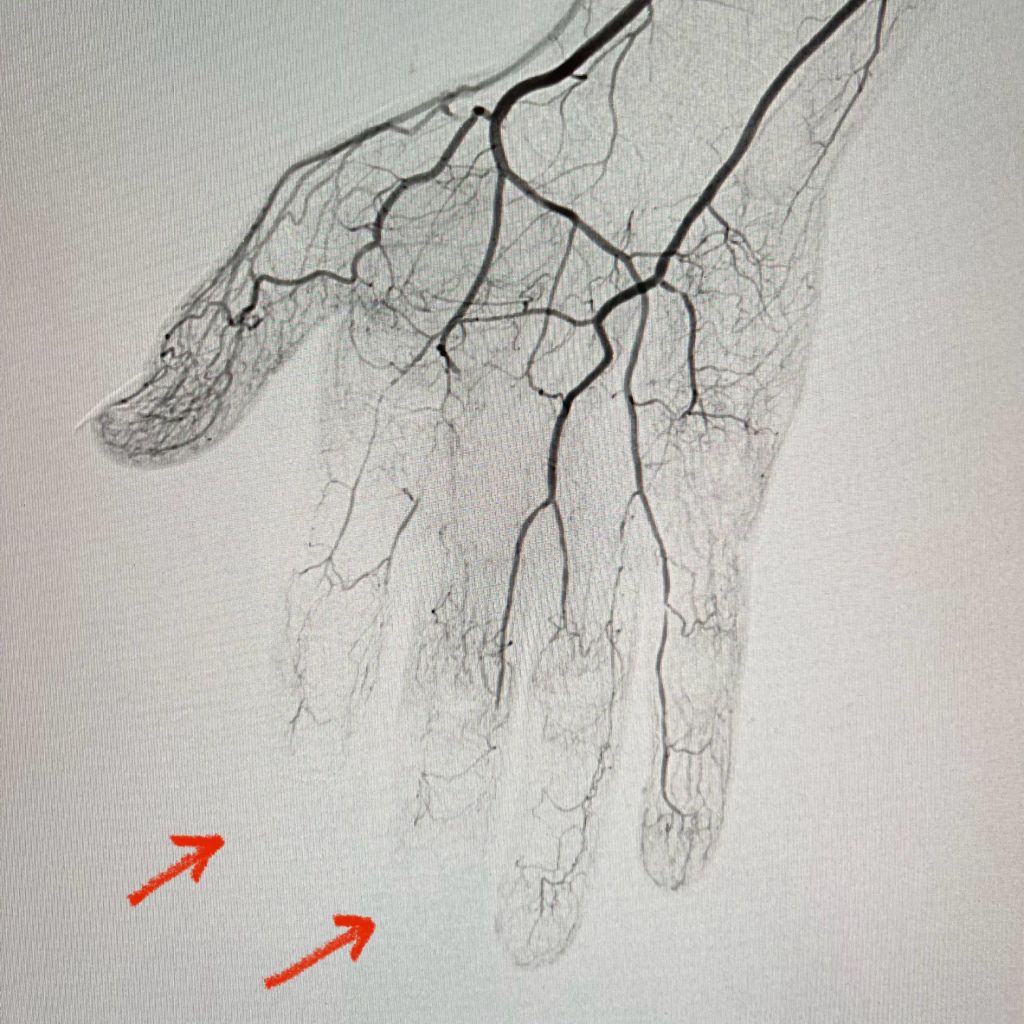

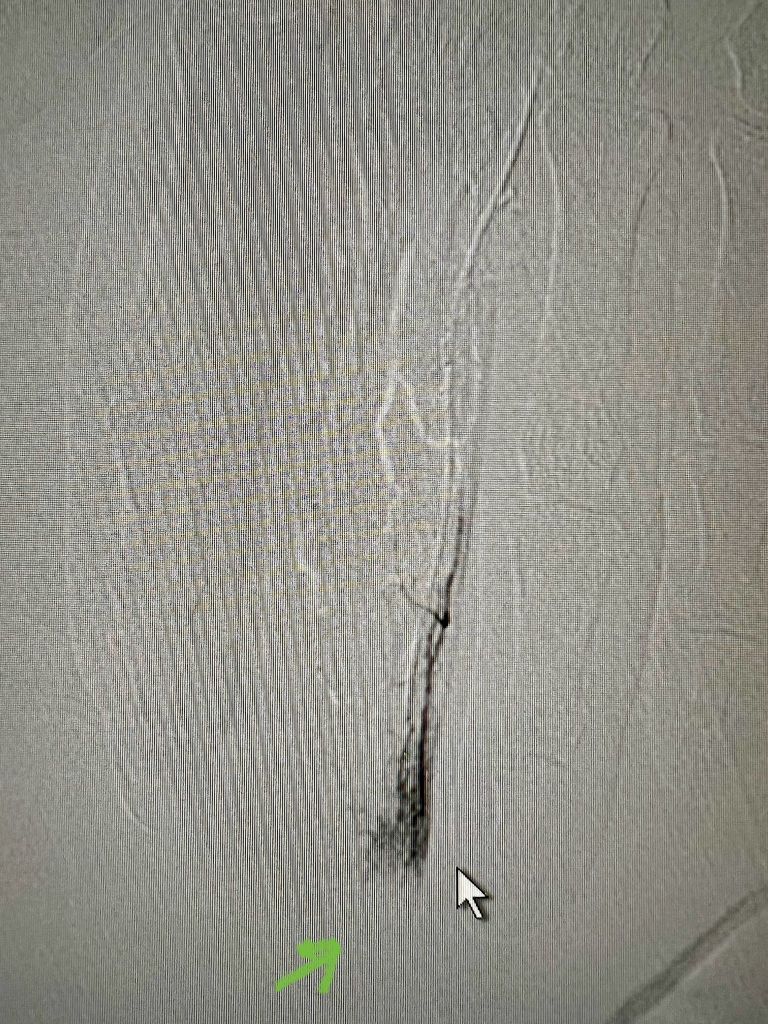

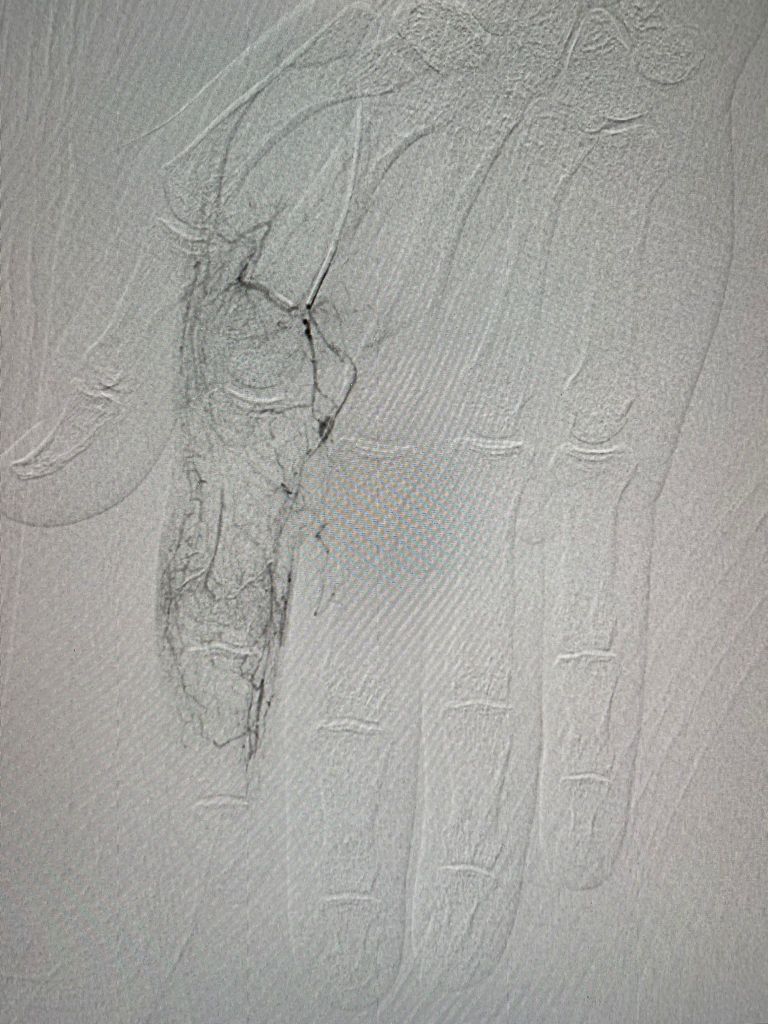

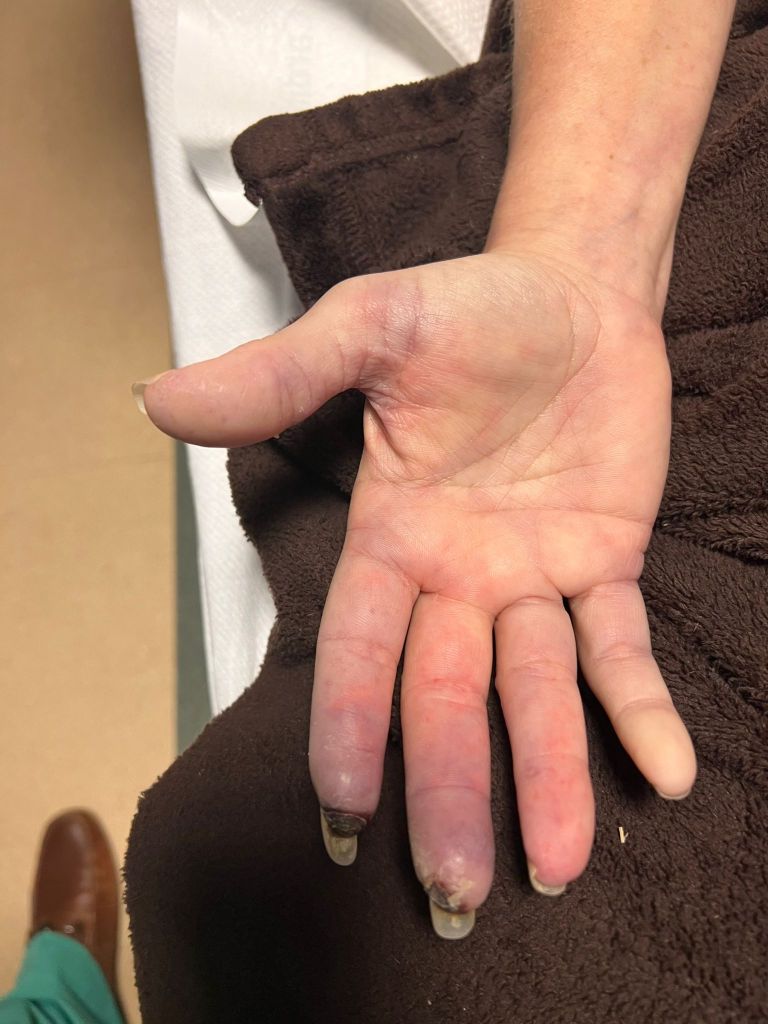

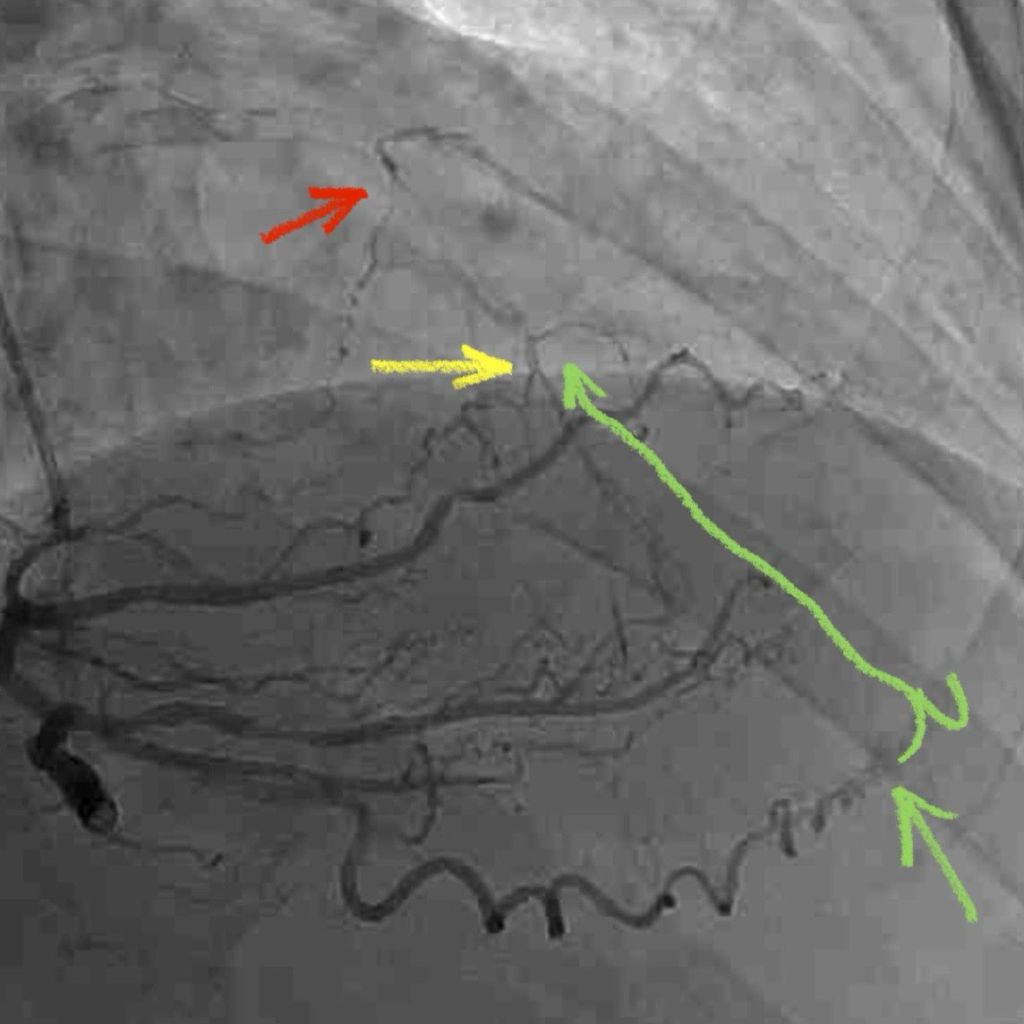

Four days later, the patient was found dead in his parked vehicle. The autopsy identified a complete right coronary artery occlusion (assumed acute), 60 percent left anterior descending artery stenosis, left ventricular hypertrophy, and heart chamber dilatation. The cause of death was listed as coronary artery thrombosis due to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, with morbid obesity contributing.

Allegations

A lawsuit was filed against the cardiologist alleging:

- failure to obtain an adequate family history and detailed symptoms;

- disregard for ominous EKG findings; and

- failure to refer patient to the hospital for cardiac evaluation.

Legal implications

Two of the three consultants for the defense felt that Cardiologist A provided adequate treatment to the patient. They noted that given the patient’s history, physical exam, and EKG, there was no evidence of acute coronary ischemia. Reasonable care would include a stress test, EKG, and hypertension treatment, as there were no indications the patient required admission to the hospital.

However, the third consultant expressed that the defendant should have discussed admission with the emergency department for further evaluation, given that the patient was morbidly obese with severe hypertension, chest pain, and an abnormal EKG. This consultant also felt that Family Physician A should have had the patient emergently transported to the ED for evaluation instead of referring him to cardiology.

Consultants for the plaintiff also expressed their concern about the EKG results and that the patient should have been immediately admitted to the telemetry unit for a cardiac workup. These consultants argued that the patient would have had a higher chance of survival if he had been sent to the ED right away.

Another point of concern for the defense was documentation. There were conflicts between Cardiologist A’s documented patient history and the history obtained by the family physician. Additionally, there was a chest pain questionnaire in the family physician’s chart that was not sent with the EKG report. Cardiologist A’s chart did not contain the questionnaire, and it did not reflect any inquiries about reports of chest pain when examining the patient.

Disposition

The case was settled on behalf of Cardiologist A.

Risk management considerations

Communication between physicians regarding patient care should be comprehensive and include all necessary information. In urgent situations, such as in this case, reviewing the patient’s medical record and history can aid in providing the best treatment. Cardiologist A failed to review and document an accurate patient and family history that may have indicated a more emergent response and hospital admission.

According to the plaintiff’s consultants, the two EKGs obtained for the patient (at the offices of Family Physician A and Cardiologist A) indicated the need for a more emergent response by both physicians. Also, had Family Physician A sent the patient’s chest pain questionnaire to Cardiologist A, the cardiologist may have been alerted to a potentially serious underlying condition in the patient.

Cardiologist A’s charting lacked documentation regarding the severity of the patient’s chest pain. In addition to missing Family Physician A’s chest pain questionnaire, Cardiologist A’s records were also missing the patient’s history of pain that day and over the past two months. This information — had the cardiologist been aware — would have indicated a need for either further testing that day or transporting the patient to the hospital.

When caring for patients, it is essential to obtain comprehensive histories. If you have a prior relationship with the patient, like Family Physician A, it is important to review the patient’s history at every visit and to add anything new that may have happened since the previous visit.

This patient had a significant family history of heart disease with one parent having a prior heart attack and a coronary artery bypass surgery. This should have indicated to the cardiologist that the patient was at higher risk for occluded vessels, when matched with the symptoms he was experiencing at his visit.

There was also a delay in recommended follow up. The importance of prompt follow up needed to be stressed to the patient. Cardiologist A said the patient needed to follow up in three days. The staff should not have allowed the patient to push the return visit date past the 3-day mark without checking with the physician first. Educating the patient on the importance of timely follow-up and the need to be seen in three days may have prompted him to take the situation more seriously.